- Curveball Chronicles

- Posts

- The River Belongs on a Map, Not a Softball Field - and - How Seasonal “Phases” Will Help Your Development

The River Belongs on a Map, Not a Softball Field - and - How Seasonal “Phases” Will Help Your Development

‘Total Reading Time: 8 minutes

Happy Monday! Here we are - the last Monday in July and the eve of August before heading back to school. Today we’re looking at the concept of pitching into “the river” and how it’s harmful for our pitchers. Along with how breaking your season up into “phases” will give you a huge advantage in your development.

So Let’s Go!

“The River” Belongs on a Map - Not a Softball Field!

In softball we live with this crazy fear of our pitcher’s throwing their pitches into the strike zone. We tell them that strikes will get HIT - and at the same time we lose our minds if they walk anyone.

So, pitchers can’t throw strikes and they can’t throw balls. Well, there’s nothing left - those are our only two options.

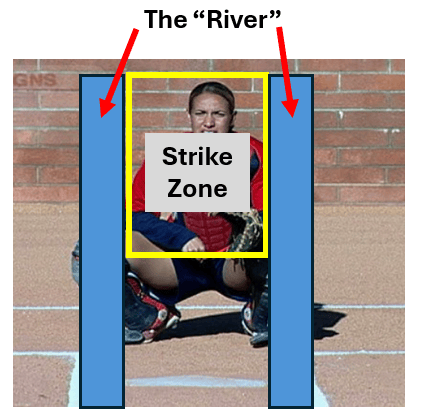

Then we come up with this insane concept of “the river” and tell our pitchers that’s where they’ve got to live - outside the strikezone, but not too outside. Just a very small, specific area outside the strikezone. Because again, we believe that inside the strikezone is not only bad, it’s DANGEROUS!

This makes our pitchers really good at:

Being Afraid

Pitching Balls

Falling Behind

Walking Batters

and Avoiding the Strike Zone

Bad pitches (aka those that are constantly outside the strikezone) can only get bad hitters out, but good hitters take them for balls.

Balls are for batters, strikes are for pitchers.

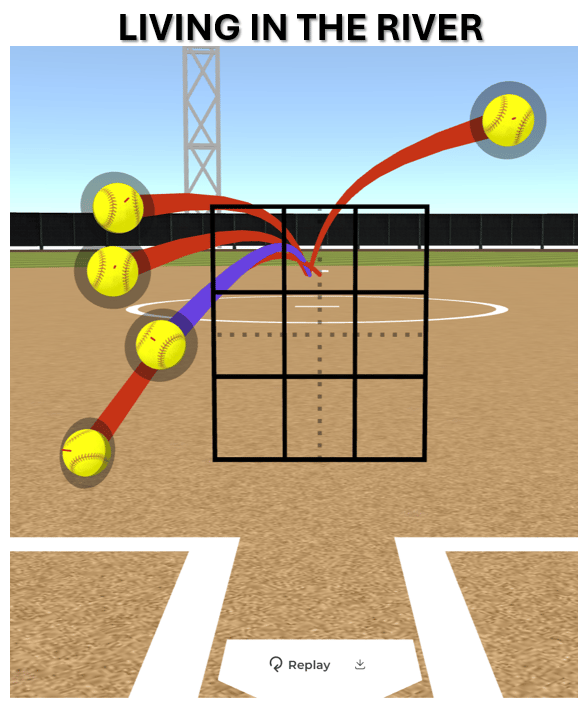

When we constantly ask our pitchers to throw outside of the zone, not only do our pitchers struggle to ever get ahead and get hitters out, but they adopt our fear of pitching into the strike zone.

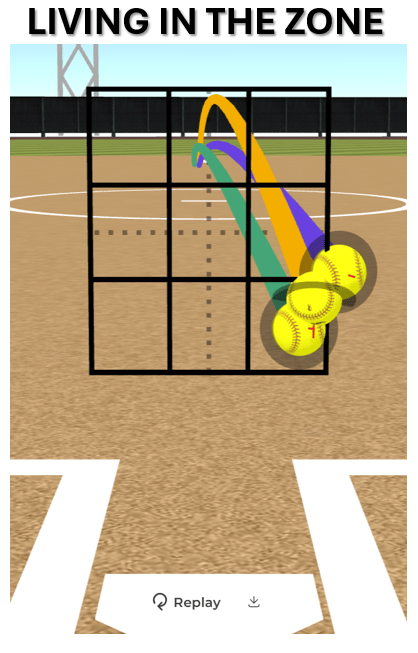

We HAVE to throw pitches into the zone! We have to see the strike zone as the the place on the field where we flourish! We’ve got to re-frame the strike zone as our friend.

Sure, you’re going to throw a pitch outside the zone, into the shadow edges (which I like better than “the river”), but that’s occasional and purposeful:

Throw to batters that swing a lot

To setup a pitch in the opposite part of the zone

To change a batter’s eye

To batters with poor discipline

But those reasons are limited, occasional and very purposeful in regards to the hitter. Simply being afraid to throw a pitch into the strike zone and therefore constantly living in “the river” is a thought-process for disaster as a pitcher.

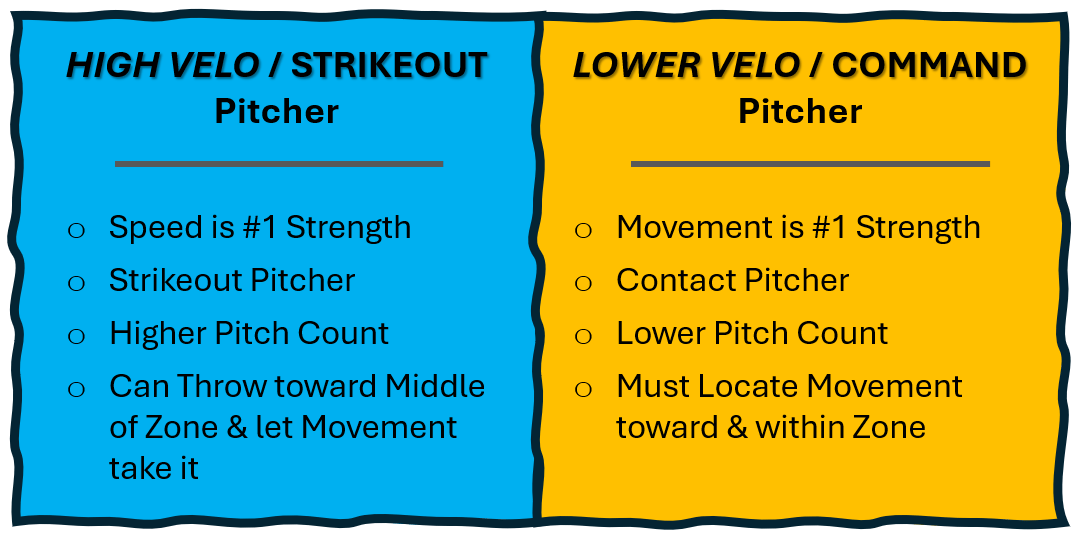

And depending on the type of pitcher determines just “how” they throw into the zone. How fast you throw or how much command and movement you have determines how much you can either throw dead into the zone, or pick your way around the different parts of the strikezone.

High Velo / Strikeout Pitchers - can afford to throw the ball toward the middle of the zone and let their speed aid any lack of movement they might have. High Velo pitchers can also live outside the zone more successfully because of their velocity.

Low Velo / Command Pitchers - without the benefit of +velo, these pitchers must rely on their ability to locate their movement within varying parts of the strike zone. The slower velocity allows hitters more time to decide if they’ll swing, so the pitch movement is what will deceive the hitters.

Let’s jump to baseball for a second and look at Tarik Skubal, one of the best pitchers in the MLB right now. Skubal throws for the Detroit Tigers and is walking batters at a Greg Maddux-like rate of 3.3% while striking out batters at a Randy Johnson-esque clip of 34%. Each of those rates rank first among qualified pitchers.

Skubal says his walk rate keeps improving because he trusts to throw his stuff into the strike zone more. To succeed in today’s game, he says a pitcher must have the stuff to pitch within the confines of the zone, not the shadow-y edge (aka the river).

THE SHADOW ZONE:

We call it the “river” and Major League Baseball calls it the “shadow” zone. Baseball Savant defines it as that murky area a few inches on either side of the strike zone.

This year in the MLB, 42% of pitches that fall into this shadow zone - that aren’t swing at - are called strikes. That means 58% of pitches in that area are balls.

THE AVEARAGE MLB MISS DISTANCE:

The average miss distance by MLB pitchers is about a foot. This is important because if that’s how much Major League pitchers miss then we can safely assume our pitcher’s miss distance is much greater.

Most of this “miss distance” is the result of movement taking a pitch more, or in a different direction than the pitcher intended.

Now flash back to “the river”. If we’re calling our pitcher to throw into this zone knowing they’ll probably miss by at least 10-12 inches, then they’re more likely to throw behind the batter than to hit a spot in the strike zone.

Instead, asking pitchers to throw into the zone and let their movement run the ball, we still have some zone left for a strike.

“I am a little old school. I do think you need to throw strikes and get ahead. The game needs to be simple in terms of first-pitch strike, and getting to leverage,” Skubal said. “But at the same time, you have to have pretty good stuff to pitch in this game now, because the strike zone is the smallest it’s ever been, and with ABS (auto Ball & Strike) coming, it’s only going to get smaller. You have to be able to get a miss, and compete in that zone. “

Let’s start focusing on our pitchers throwing within the various parts of the zone, and leave the river for a map.

How Seasonal “Phases” Will Help Your Development

Last week we took a deep-dive into planning your upcoming season, and this week we’ll look at how breaking your season into chunks, or phases will help.

We enter the season with all kinds of plans and motivation, only to have the day-to-day of it all turn our plans into April before we know it.

So consider “phases” as a way to break up your season and not only make your planning easier, but also allow you to notice more quickly when they’ve gotten off track.

Of course you can create your own phases, but here are 10 phases that are commonly used by successful programs:

Phase 1: August/Sept Individuals

Phase 2: Fall Team Practice

Phase 3: Oct/Nov Individuals

Phase 4: Winter Break

Phase 5: January Team Practice

Phase 6: Pre-Season

Phase 7: Conference

Phase 8: Regionals

Phase 9: Supers

Phase 10: WCWS

You should adjust these based on your program. For instance, if it isn’t realistic that your team goes to the WCWS, then you can either drop your phases down to 9, or else break up your Conference schedule into 2 parts and making Supers your 10th phase.

It isn’t important how many you have, or what they’re called, what matters is that you logically break up your season into small parts that allow you to:

more specifically target the growth needed during this phase

how you’ll test for that growth

what you’ll do with each pitcher to create growth within each phase

Thanks for reading this week’s Curveball Chronicles. I hope it’s helped give you some insight to help your pitchers, and to give yourself some encouragement, knowledge and grace.

Go make this a Great week!

Missed some previous issues? Don’t worry, I’ve got them all for you on my website: https://pitchingcoachcentral.com/curveball-newsletter/

Reply